-

Curated by Hettie Judah

-

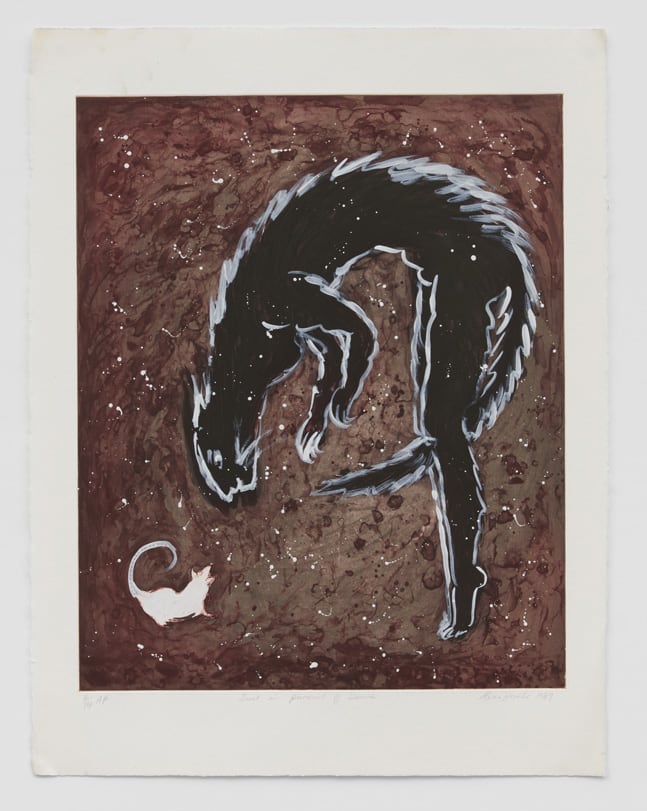

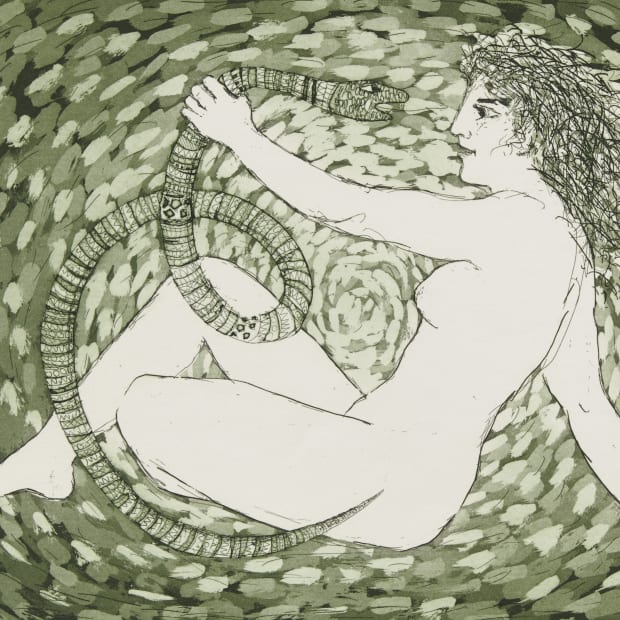

"A goddess confronts patriarchy: she is naked and magnificent; he a great serpent, phallic, coiled, bejewelled. She looks apt to bite."

- Hettie Judah

-

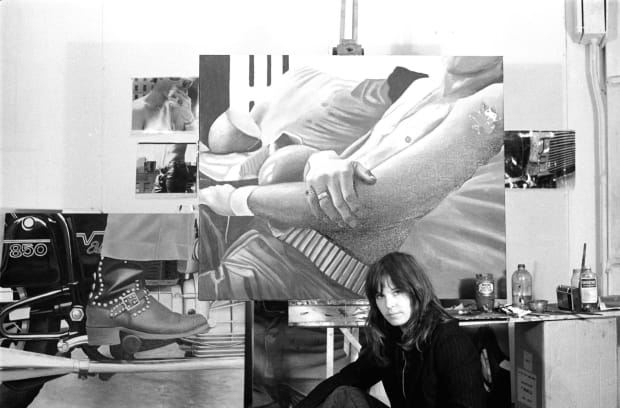

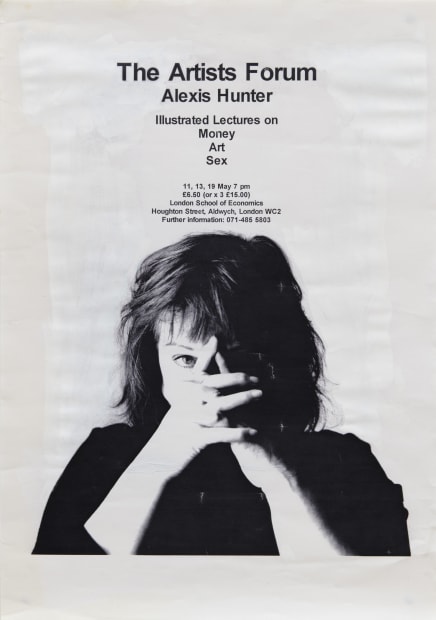

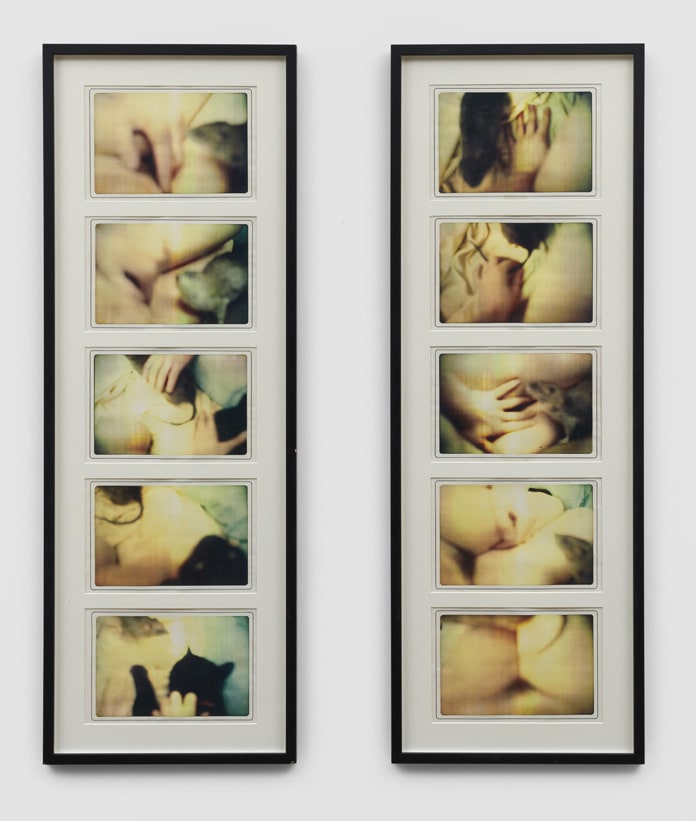

Alexis HUNTER

A Goddess confronting Patriarchy, 1983Etching38 x 56 cmEdition of 24 -

-

-

-

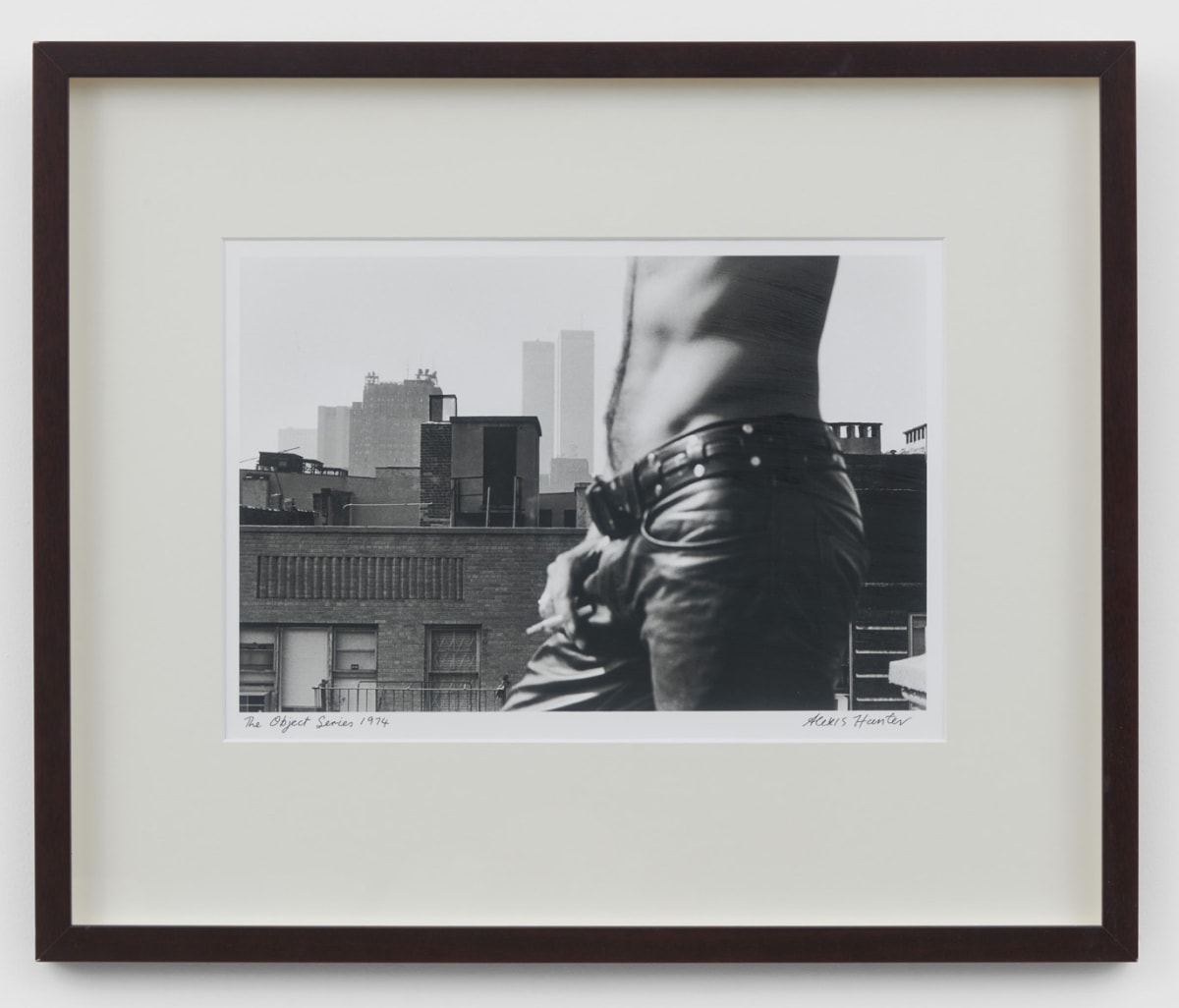

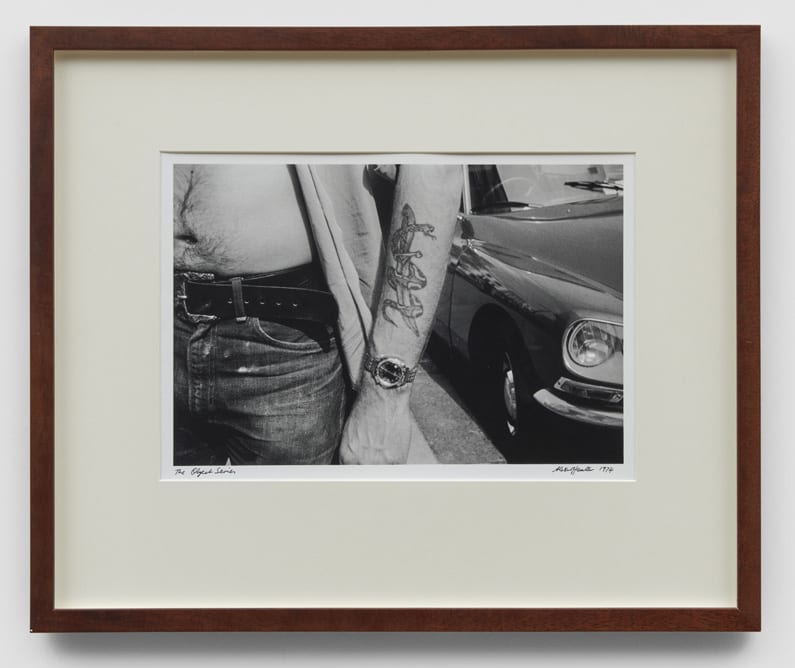

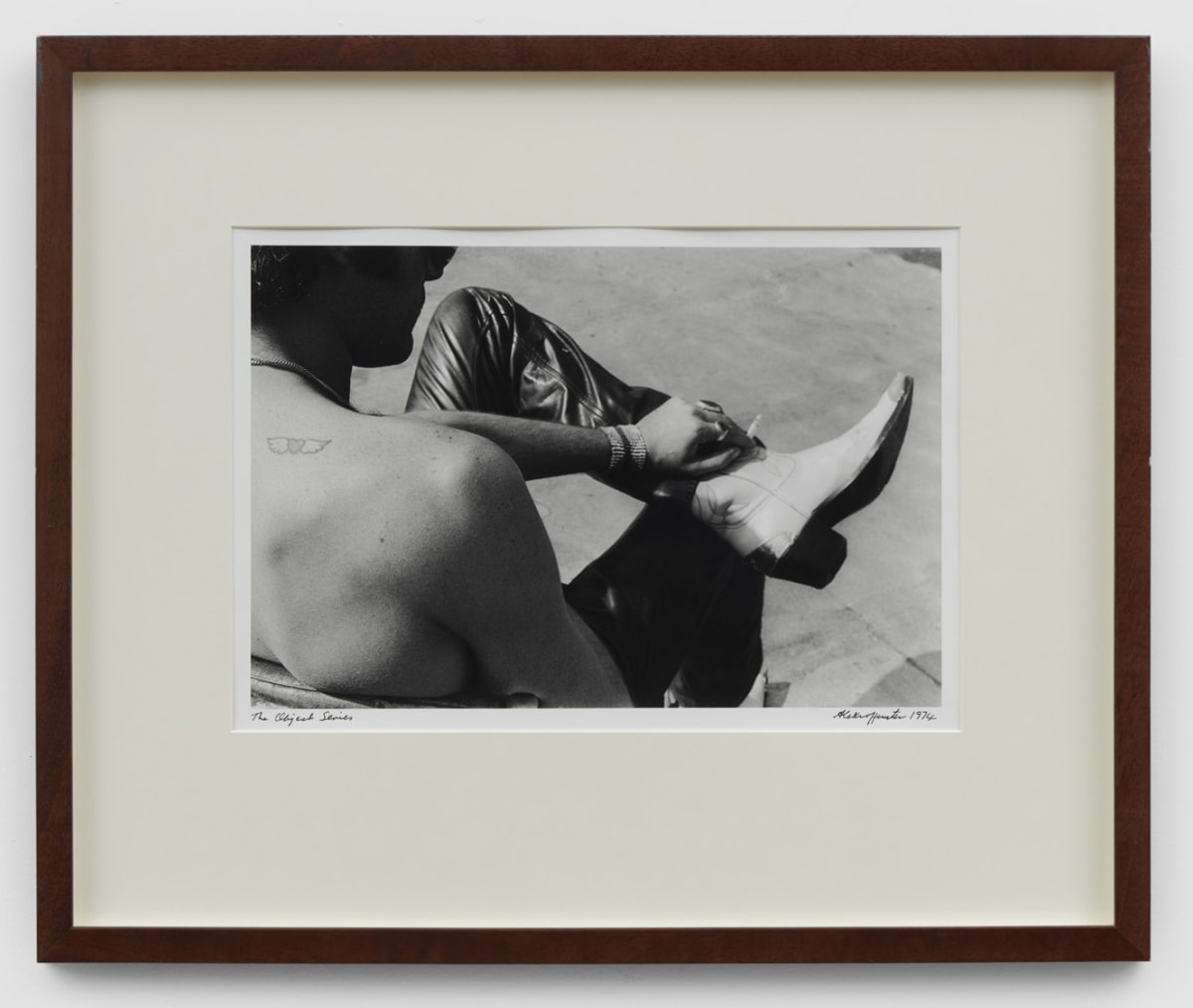

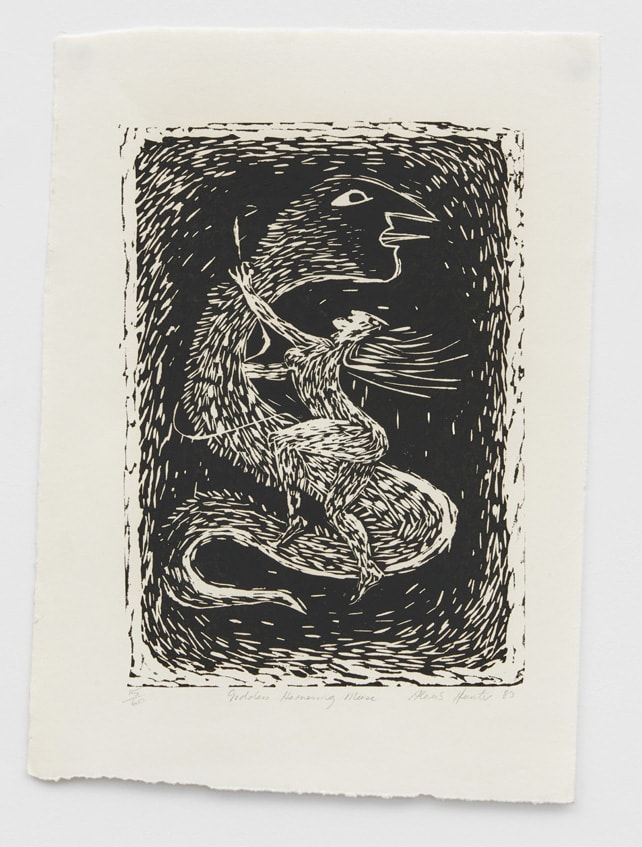

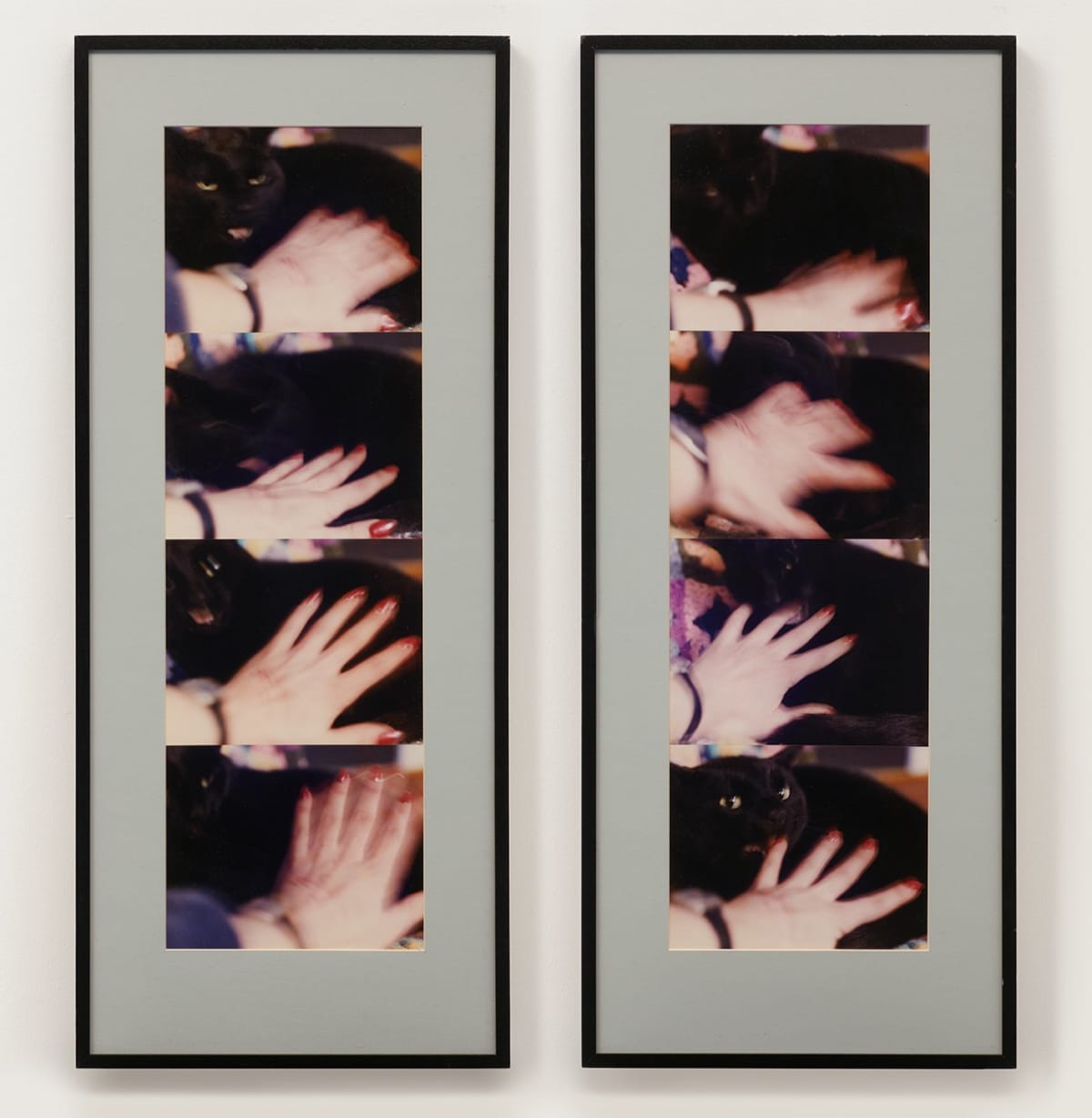

Alexis HUNTER

Goddess Harnessing Muse, 1983Linocut39 x 28 cmEdition of 60 -

-

-

-

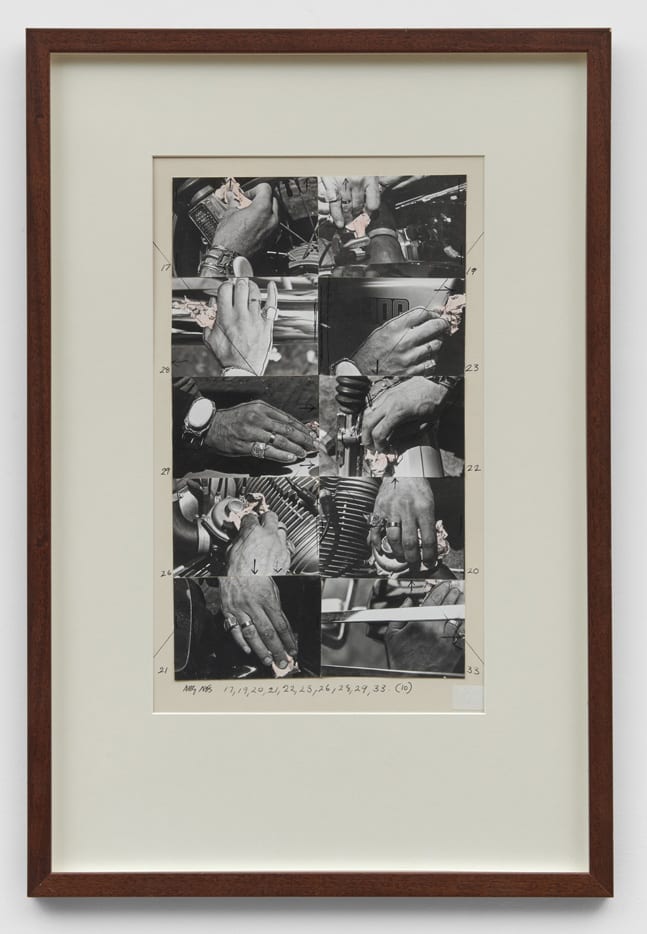

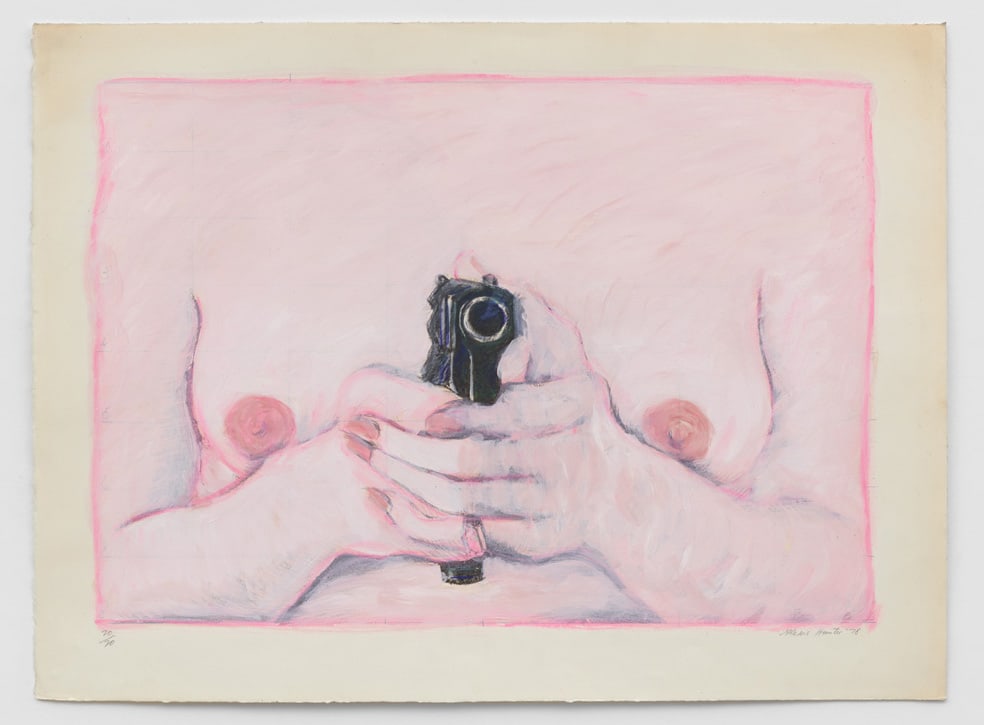

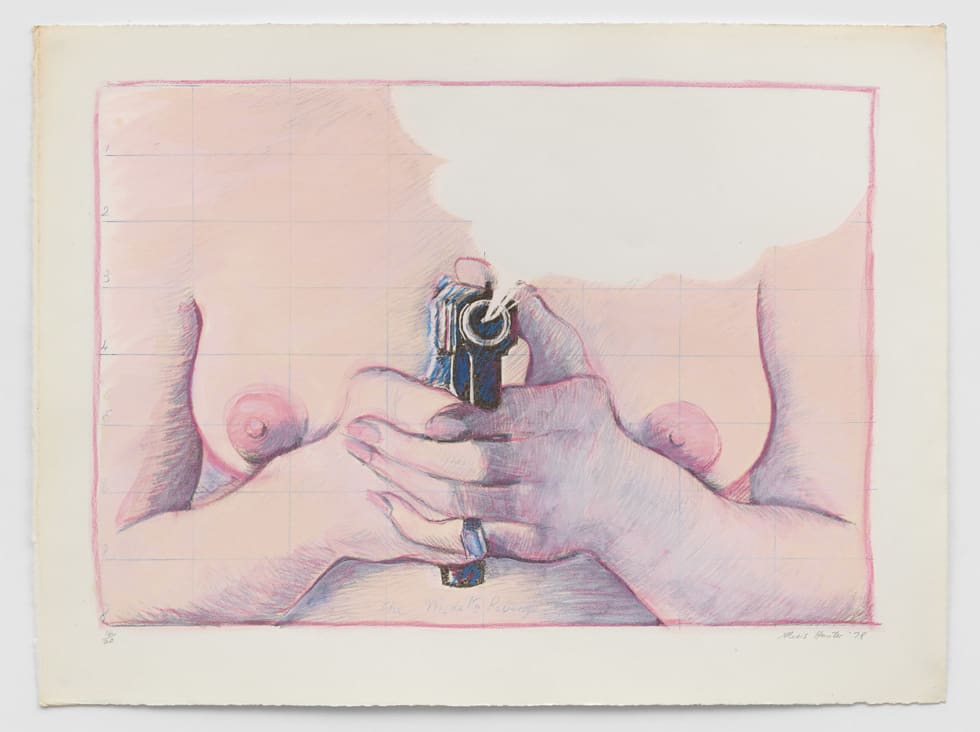

Alexis HUNTER

Tits and Bums, 1986Ink and photo-collage mounted on paper, vintage29.8 x 20.9 cm -

-

1. Artist's Statement, Camden Town (1982) cited in Elizabeth Eastmond's Alexis Hunter: Fears/ Dreams/ Desires (1989)

2. Catalogue for the British Council exhibition Fantasy (1994)3. Interview with John Roberts in The Impossible Document: Photography and Conceptual Art in Britain 1966-76 (Camerawords, 1997) cited in Alexis Hunter: Radical Feminism in the 1970s (Norwich Gallery, 2006)

4. Catalogue for the British Council exhibition Fantasy (1994)

Text by Hettie Judah.

Saltoun Online